Abstract

Background

Approximately 25% of adults in the United States have a disability that limits function and independence. Oral health care represents the most unmet health care need. This population has been found to have decreased oral health outcomes compared with the general population.

Methods

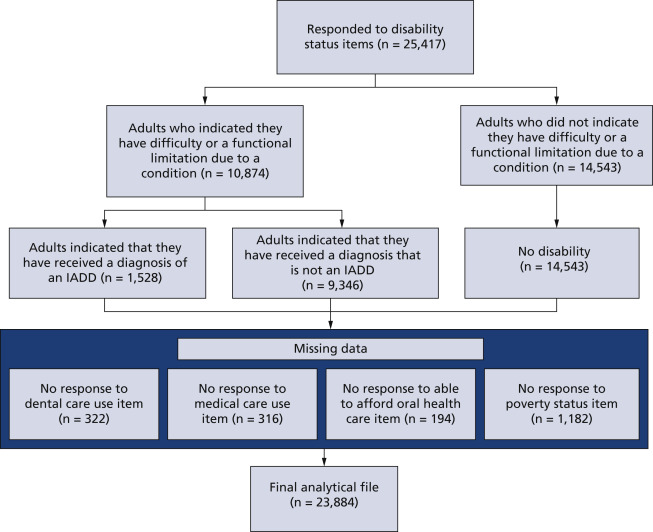

The authors used the 2018 adult National Health Interview Survey to assess the association between disability status and dental care use (dental visit within or > 2 years). Disability status was categorized as adults with an intellectual, acquired, or developmental disability (IADD) that limits function, other disability that limits function, or no disability, on the basis of diagnoses of birth defect, developmental diagnosis, intellectual disability, stroke, senility, depression, anxiety, or emotional problem, all causing problems with function.

Results

Adults with an IADD with functional and independence-limiting disabilities experienced higher crude odds of going 2 years or more without a dental visit than adults without disabilities (odds ratio [OR], 2.29; 95% CI, 1.96 to 2.67). This association was part of a significant interaction and was stronger among those with IADDs who could afford oral health care (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47 to 2.14) than among those who could not afford oral health care (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.88 to 1.67; P value of interaction <.01).

Conclusions

Adults with IADDs have decreased access to oral health care compared with adults with other disabilities or without disabilities. The inability to afford oral health care lessens the impact of disability status.

Practical Implications

Dentists can use this study to understand the implications of IADD diagnoses on dental care use and make efforts to facilitate care for these patients.

Key Words

Abbreviation Key:

IADD (Intellectual acquired or developmental disability), NA (Not applicable), NHIS (National Health Interview Survey)

For people with disabilities, oral health care has been found to be among the most common unmet health care needs.

- Kancherla V.

- Van Naarden Braun K.

- Yeargin-Allsopp M.

,

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

,

- Ward L.M.

- Cooper S.A.

- Macpherson L.

- Kinnear D.

Any diagnosis of disability may be associated with inferior oral health outcomes compared with the general population. Disability is defined as a condition that limits the activities that a person is able to perform and limits their participation and interaction in the world around them.

Intellectual, acquired, or developmental disabilities (IADDs) are defined as “disabilities characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior.”

- Schalock R.L.

- Luckasson R.

- Tassé M.J.

A disability is “developmental” when it originates before the age of 22 years, and “acquired” when it originates at age 22 years or later.

- Schalock R.L.

- Luckasson R.

- Tassé M.J.

Some examples of developmental diagnoses are cerebral palsy, autism, and Down syndrome; examples of acquired disabilities include senility and disabilities secondary to a stroke.

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

,

- Kane D.

- Mosca N.

- Zotti M.

- Schwalberg R.

Adults with IADDs have been reported to have a 56% through 92% prevalence of periodontal disease, score of 8 through 25 on the decayed, missing, and filled tooth index, and up to 73% prevalence of edentulism.

- Ward L.M.

- Cooper S.A.

- Macpherson L.

- Kinnear D.

,

- Alves N.S.

- Gavina V.P.

- Cortellazzi K.L.

- Antunes L.A.A.

- Silveira F.M.

- Assaf A.V.

,

- Morgan J.P.

- Minihan P.M.

- Stark P.C.

- et al.

These conditions are also associated with decreased quality of life, including oral pain and psychological discomfort.

- Ward L.M.

- Cooper S.A.

- Macpherson L.

- Kinnear D.

,

- Couto P.

- Pereira P.A.

- Nunes M.

- Mendes R.A.

Poor oral health is associated with poor overall health, putting people with IADDs at additional risk of decreased health outcomes.

,

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

,

- Schalock R.L.

- Luckasson R.

- Tassé M.J.

,

Oral health status for adults with IADDs has been well described, but the root causes for the disparities in status are not well understood.

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

,

- Schalock R.L.

- Luckasson R.

- Tassé M.J.

,

- Couto P.

- Pereira P.A.

- Nunes M.

- Mendes R.A.

The life span of adults with disabilities is expanding due to improvements in chronic health care management, so more adults with IADDs face these unmet needs.

- Chávez E.M.

- Wong L.M.

- Subar P.

- Young D.A.

- Wong A.

Barriers to oral health care for adults with an IADD include poor access to care, insufficient education and training of dentists, limited behavior tolerance of patients, affordability of care, and lack of understanding about the need for care.

- Ward L.M.

- Cooper S.A.

- Macpherson L.

- Kinnear D.

,

,

- Casamassimo P.S.

- Seale N.S.

- Ruehs K.

,

,

- Krause M.

- Vainio L.

- Zwetchkenbaum S.

- Inglehart M.R.

,

,

- Frenkel H.

- Harvey I.

- Needs K.

,

- Sermsuti-Anuwat N.

- Pongpanich S.

These barriers have been described in the literature, but have not been well investigated.

- Casamassimo P.S.

- Seale N.S.

- Ruehs K.

,

,

- Krause M.

- Vainio L.

- Zwetchkenbaum S.

- Inglehart M.R.

It is not understood how these barriers to care affect dental care use and frequency of dental visits for adults with an IADD.

Our aim was to assess the relationship between disability and oral health care use, with a special focus on those with IADDs.

to answer the following question: What are the associations between disability status and use of dental services within 2 years for adults in the United States? We aimed to describe the distribution of function and independence-limiting disability diagnoses among adults and evaluate the association between IADD status and oral health care use within 2 years. We assessed population-based access to oral health care and the association of disability status with dental care use, which was measured as adults having seen a dentist within the past 2 years. We examined demographic characteristics and poverty status as potential confounders. Adults’ ability to afford oral health care, adults’ ability to respond to the survey on their own, and adults’ duration since their last physician visit were assessed as effect modifiers of the association between disability status and of oral health care use within 2 years.

Methods

Study design

We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting observational studies.

- von Elm E.

- Altman D.G.

- Egger M.

- Pocock S.J.

- Gøtzsche P.C.

- Vandenbroucke J.P.

- STROBE Initiative

The NHIS is an annual cross-sectional complex sampling of all civilian noninstitutionalized people in the United States. The survey collects demographic, occupation and employment, health status, and health care use data to assess for health- and health care–related issues. There are separate surveys for adults and children, as well as household and family questionnaires. Adult data represented people 18 years and older, comprising 25,417 adults, and were weighted for analysis.

Exposure and outcome

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

Other disabilities included any other medical diagnosis indicated in the NHIS survey not included in IADD diagnoses with functional limitation due to that diagnosis.

However, according to Healthy People 2020, fewer than 45% of people older than 2 years visited a dentist within the past year in 2007 and, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, substantial disparities in access to oral health care exist among people of different racial and ethnic groups, socioeconomic groups, and education levels for oral health care.

,

Therefore, we dichotomized the study outcome of dental care use into time frames of less than or equal to 2 years and greater than 2 years since the last dental visit to capture a broader and more conservative reference of timely dental care use. Age was categorized into groups 18 through 25 years, 26 through 44 years, 45 through 64 years, and 65 years and older. Adults’ regions were reported according to categories provided in the data set, which were Northeast, Midwest, South, and West. Race or ethnicity was categorized into non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other, or Hispanic. Adult proxy status was dichotomized into self and alternate, ability to afford oral health care was dichotomized to yes or no, and time lapse since the last medical visit was dichotomized to less than or equal to 2 years or greater than 2 years to match the time lapse for dental care use.

the following 2 questions were asked regarding use of oral health care services: “About how long has it been since you last saw a dentist? Include all types of dentists, such as orthodontists, oral surgeons, and all other dental specialists, as well as dental hygienists” and “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed any of the following [dental care, including check ups], but didn’t get it because you couldn’t afford it?”

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

,

- Casamassimo P.S.

- Seale N.S.

- Ruehs K.

,

,

- Krause M.

- Vainio L.

- Zwetchkenbaum S.

- Inglehart M.R.

Data analysis

Data analyses were completed using statistical software (SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute). For analyses, P values of .05 or less were considered statistically significant. Descriptive analyses of the study population and logistic regression analyses were implemented to examine the association between disability status and duration since the last dental visit. The crude association between disability and duration was assessed via Pearson χ2 test with categorical variables of disability status and dental care use within 2 years. Weighted multiple logistic regression was used to test the association between disability status and dental care use, controlling for age group, sex, race or ethnicity, geographic region, and poverty status, using NHIS person file for poverty status measure for sample adults.

Diagnosis of IADD includes attention deficit disorder/attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, other mental problem, birth defect, developmental diagnosis (for example, cerebral palsy), senility, dementia, Alzheimer disease, intellectual disability, mental retardation, depression, anxiety, emotional problem, or stroke.

- da Rosa S.V.

- Moysés S.J.

- Theis L.C.

- et al.

,

,

- Krause M.

- Vainio L.

- Zwetchkenbaum S.

- Inglehart M.R.

Confounding was evaluated by means of percentage of change of the log transformed OR, adjusting for the specified covariate, with a difference of 10% from the crude association to the adjusted log OR and a P value of <.20 for the association between the covariate and duration since last dental visit. Final modeling by means of weighted multiple logistic regression was stratified according to the adult’s ability to afford oral health care and was controlled for age group, sex, race, and poverty status.

Results

Table 1Weighted prevalence of disability according to demographic characteristics.

Nearly all adults (96.9%) responded for themselves, and 1.5% relied on an alternate respondent (1.5% missing). In terms of ability to afford care, 87.7% were able to afford oral health care and 11.5% were unable to afford oral health care. Most adults (91.4%) reported visiting a physician within the last 2 years compared with 7.2% who had not (1.2% missing). Ability to afford oral health care was the only 1 of these 3 covariates that was a significant effect modifier of the association between disability status and dental care use (P < .01).

Table 2Weighted unadjusted crude association between disability status and having more than 2 years since the dental visit.

Adjusted for age group, sex, race and ethnicity, and poverty status.

between disability status and dental use, stratified according to ability to afford oral health care.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the only analysis to investigate the effect of disability on oral health care use for adults with disabilities in the following 3 distinct categories: IADDs, other disabilities with functional limitations, and no disabilities. Our results showed that there are significant implications of a diagnosis of an IADD that limits a person’s independence or function on that person’s use of oral health care. Adults with IADDs are less likely to visit a dentist than those with other disabilities or no disabilities. However, for adults who cannot afford oral health care, oral health care use is not statistically different for adults with disabilities compared with adults without disabilities. A separate analysis of nonresponse revealed that participants with no poverty status data were no more likely to have an IADD than were those who responded to the poverty status items.

- Kane D.

- Mosca N.

- Zotti M.

- Schwalberg R.

,

- Casamassimo P.S.

- Seale N.S.

- Ruehs K.

,

- Krause M.

- Vainio L.

- Zwetchkenbaum S.

- Inglehart M.R.

,

- Williams J.J.

- Spangler C.C.

- Yusaf N.K.

,

- Lim M.

- Liberali S.

- Calache H.

- Parashos P.

- Borromeo G.L.

Adults with IADDs are often insured via Medicaid for medical and dental coverage.

- Alves N.S.

- Gavina V.P.

- Cortellazzi K.L.

- Antunes L.A.A.

- Silveira F.M.

- Assaf A.V.

This coverage is widely variable according to state, including reimbursement rate and extent of coverage. Some states have more robust dental coverage in their Medicaid programs, and some states offer none. Medicaid dental coverage may help improve access to oral health care in states with a high density of dentists and strong Medicaid coverage.

- Wehby G.L.

- Lyu W.

- Shane D.M.

However, dental providers may choose not to participate in the Medicaid program, owing to limited coverage and reimbursement, which then limits the financial feasibility of adults with IADDs and other disabilities to be able to afford necessary oral health care.

- Kancherla V.

- Van Naarden Braun K.

- Yeargin-Allsopp M.

,

- Ward L.M.

- Cooper S.A.

- Macpherson L.

- Kinnear D.

,

- Frenkel H.

- Harvey I.

- Needs K.

,

- Waldman B.H.

- Perlman S.P.

Without accepted insurance, oral health care represents considerable out-of-pocket costs. These costs may be untenable for adults with function- and independence-limiting conditions, which may impede their ability to work or earn an income, inhibiting dental care use. The disproportionate barriers to oral health care for adults with IADDs, especially those who are covered via Medicaid, could be improved with more closely integrated medical and oral health care, which could prevent differences in medical vs dental visits.

- Williams J.J.

- Spangler C.C.

- Yusaf N.K.

The second most prevalent barrier (18%) to oral health care was finances, and the third most prevalent barrier (14%) identified was wait time.

- Williams J.J.

- Spangler C.C.

- Yusaf N.K.

This study applied to children mainly, but parents of adults with special needs aged 18 through 26 years were also included. Although IADDs are only a subset of special needs, adults with IADDs experience similar barriers as children and adults with more broad special needs, which contributes to the limited dental care use that adults with IADD face.

- Lim M.

- Liberali S.

- Calache H.

- Parashos P.

- Borromeo G.L.

Providers broadly lacked the training, experience, and support to routinely and adequately provide care for these patients. Adults with IADDs present a specific challenge to oral health care providers, as they may be unable to behaviorally tolerate care, follow instructions, or transfer to a dental chair.

- Ward L.M.

- Cooper S.A.

- Macpherson L.

- Kinnear D.

,

However, it is telling that even in a country in which special care dentistry is a recognized specialty there is a reported lack of education, experience, training, and support for dentists to treat patients with disabilities, which creates a dental workforce barrier to provide care for these patients.

- Lim M.

- Liberali S.

- Calache H.

- Parashos P.

- Borromeo G.L.

Our study does have some limitations. NHIS data are self-reported and are difficult to validate. NHIS does not directly assess for or measure need for oral health care, provision of dental treatment, or dental outcomes. Due to the cross-sectional design, there is no ability to assess temporality or cause and effect. We did not consider dentist-based factors, such as geographic location or timeliness of appointments, or patient-based factors, such as patient or caregiver knowledge or motivation to address limited dental care use.

Despite these limitations, we provided a broad, publicly accessible, generalizable overview of the state of dental care use across the United States. The use of NHIS data provides a population-based overview of the duration since adults’ most recent dental visits, and clear associations are able to be assessed between dental care use and disability diagnosis status and the impact of the ability to afford oral health care. Our study is reproducible and allows inferences to be drawn about dental care use for adults with IADD compared with other disabilities, which can help target future studies that may be able to improve access and oral health outcomes. Although we cannot provide any inference about oral health care need and the temporality of oral health care, we found a clear and significant association between disability and limited use of oral health care.

Practical Implications

Our results showed that barriers to oral health care exist for adults with IADDs and may be beneficial in advocacy to improve the condition and well-being of adults with IADDs. Our study can help guide future research to understand the specific patient and clinician-centered issues that limit patient use, as well as hinder providers from being able to treat these patients.

Practitioners can use our study to better understand the impact of receiving a diagnoses of IADD on oral health care use, incorporate methods and equipment to facilitate the care of adults with IADDs more broadly, and increase their capacity to treat adults with IADDs and other disabilities. Similarly, dentists could become Medicaid providers to facilitate their treatment of adults with IADDs and other disabilities. They could implement the data to advocate for increased funding for programs targeting adults with IADDs, including broader Medicaid coverage, as well as increased benefits to remove some of the financial burden of oral health care from the patient and improve access to care more broadly.

Conclusions

Adults with disabilities are a faction of patients that face disproportionate difficulties in accessing care. This impeded access can contribute to decreased health outcomes, which can lead to increased disability, increased health care costs, and decreased quality of life. It is imperative to address these issues to decrease the burden of oral disease among adults with IADDs and work to improve the overall health status of adults with disabilities.

References

Disability and health overview. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Research in developmental disabilities dental care among young adults with intellectual disability.

Res Dev Disabil. 2013; 34: 1630-1641

Barriers in access to dental services hindering the treatment of people with disabilities: a systematic review.

Int J Dent. 2020; : 1-17https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9074618

Oral health of adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review.

J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019; 63: 1359-1378

Ongoing transformation in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities: taking action for future progress.

Intellect Dev Disabil. 2021; 59: 380-391

Factors associated with access to dental care for children with special health care needs.

JADA. 2008; 139: 326-333

Analysis of clinical, demographic, socioeconomic, and psychosocial determinants of quality of life of persons with intellectual disability: a cross-sectional study.

Spec Care Dent. 2016; 36: 307-314

The oral health status of 4,732 adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

JADA. 2012; 143: 838-846

Oral health-related quality of life of Portuguese adults with mild intellectual disabilities.

PLoS One. 2018; 13e0193953https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193953

Objective and subjective oral health care needs among adults with various disabilities.

Clin Oral Invest. 2013; 17: 1869-1878

Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review.

Spec Care Dent. 2010; 30: 110-117

Dental care for geriatric and special needs populations.

Dent Clin North Am. 2018; 62: 245-267

Dental care considerations for disabled adults.

Spec Care Dentist. 2002; 22: 26-39

General dentists’ perceptions of educational and treatment issues affecting access to care for children with special health care needs.

J Dent Educ. 2004; 68: 23-28

Conceptual frameworks for understanding system capacity in the care of people with special healthcare needs.

Pediatr Dent. 2003; : 108-116

Dental education about patients with special needs: a survey of U.S. and Canadian dental schools.

J Dent Educ. 2010; 74: 1179-1189

The transition of patients with special health care needs from pediatric to adult-based dental care: a scoping review.

Pediatr Dent. 2020; 42: 101-109

Oral health care education and its effect on caregivers’ knowledge and attitudes: a randomised controlled trial.

Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002; 30: 91-100

Effectiveness of an individually tailored oral hygiene intervention in improving gingival health among community-dwelling adults with physical disabilities.

Spec Care Dent. 2021; 41: 202-209

2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2019.

June 2019

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.

Prev Med. 2007; 45: 247-251

Oral health. Healthy People 2030. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Oral health: basics of oral health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Last reviewed January 4, 2021. 2021; ()

Barriers to dental care access for patients with special needs in an affluent metropolitan community.

Spec Care Dentist. 2015; 35: 190-196

Perspectives of the public dental workforce on the dental management of people with special needs.

Aust Dent J. 2021; 66: 304-313

The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on dental visits by dental coverage generosity and dentist supply.

Med Care. 2019; 57: 781-787

Why dentists shun Medicaid: impact on children, especially children with special needs.

J Dent Child. 2003; 70: 5-9

Biography

Dr. Chavis is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

Dr. Macek is a professor, Department of Dental Public Health, School of Dentistry, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

Article Info

Publication History

Published online: May 05, 2022

Publication stage

In Press Corrected Proof

Footnotes

Disclosure. Drs. Chavis and Macek did not report any disclosures.

This study received funding from grant 1UL1TR003098-01 National Institutes of Health and the University of Maryland, Baltimore Institute for Clinical and Translational Research.

The authors thank Drs. Kathryn Barry, Surbhi Leekha, and John Sorkin, and Ms. Patricia Erickson for their guidance and feedback throughout the process of manuscript conception and analysis.

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2022.03.002

Copyright

© 2022 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

ScienceDirect

Access this article on ScienceDirect