In recent years, the public’s acceptance of oral implants has been dramatically positive. People are living longer and desire an enhanced quality of life. Being able to eat all the foods they enjoy due to improved mastication, not requiring the full dentures of their grandparents, comfortably eating and speaking at the dinner table not only with their children but with their grandchildren, provides greater confidence and enjoyment of life. Implant esthetics has also played a major role in improved appearance and social confidence.

Numerous shapes, sizes, widths, surface treatments, different groove surfaces, and other variations in design, have been developed to ensure predictable integration of the oral implant, thus facilitating prosthetic restoration and return of function. But what about the implant surgical site? How can it be optimized to ensure predictable integration?

One of the practitioner’s pressing questions today is if and when to extract. Will there be enough bone after extraction to support endosseous implants and their prosthetic restorations to function as desired? It is generally advisable to extract sooner rather than later, as there is more bone available to support an implant. In waiting you take a risk that you might end up with less bone.

The bottom line is – the more bone available, the more predictable the integration of the implant. Predictability leads to success.

In the history of dental extractions, getting the debilitated tooth out of the oral cavity as quickly and as painlessly as possible, has been paramount. After anesthesia, luxating buccal-lingually is usually the next step. The theory behind this concept is that the buccal bone is usually the thinnest zone of bone retaining the tooth, and thus it provides the least resistance. Anatomically, the buccal plate of bone is usually much thinner than the palatal or lingual. However, the easier extraction toward the buccal results in the loss of more buccal bone.

Healing depends on the blood supply, primarily from the osseous walls of the extraction site. The constant pressure from the buccal-lingual luxation leads to ischemia in the remaining thin plate of buccal bone. This ischemia leads to further resorption and loss of the buccal wall. The area will now heal with a depression in the buccal plate as well as some occlusal resorption.

The buccal depression leads to problems in oral hygiene and esthetics. Also, correct placement of the implant is now more challenging since the buccal depression has moved the remaining bone lingually (palatally). The implant needs to be placed in adequate bone to succeed. Since the implant must be located where the bone is, the placement will be lingual to the original tooth being replaced. This may create a situation requiring a prosthesis that is over- extended toward the buccal (similar to a buccal cantilever) to assure proper occlusion, potentially placing undue stress on the implant.

The goal must be to preserve as much bone as possible by preventing bone loss, especially the buccal plate, during extraction. Instruments have been developed by the author for use during extraction for this specific purpose. The Hoexter Luxators (Fig. 1) (HuFriedy USA) are designed to be used expressly in a mesial-distal motion, to avoid any buccal pressure. The design ensures that the practitioner maintains the correct angle in mesial or distal pressure on the root to be extracted, thereby ensuring a predictable result.

Fig. 1

Hoexter Luxators: series of instruments designed to facilitate the removal of roots by mesial-distal movement, allowing the preservation of buccal and lingual bone during extraction, while allowing the practitioner to visualize the operating area in comfort and ease. The instruments are available in different incised edges and sizes for various sized teeth and comfortable angulations.

The Hoexter Luxator technique relies on the premise that it is easier to extract a single root rather than a multi-rooted tooth. The practitioner, after applying local anesthetic, removes the crown of the posterior tooth horizontally at the CEJ, exposing the individual roots. Now, the Hoexter Luxator is placed (Fig. 2) in the desired location and moved with slight pressure in a M-D direction. The root will become quite mobile and easily removed. During the procedure, there should be no pressure on the buccal plate of bone. The result is a void with osseous walls intact, that can induce osseous regeneration. This includes the buccal wall as well as the mesial, distal, lingual and probably some interseptal bone. All remaining osseous walls will be productive in guiding the positive regeneration of bone. This will result in bone regeneration in the entire previous void, eliminating the resorptive depression of the buccal bone and the elimination of the oral hygiene, esthetic and restorative challenges.

Fig. 2A

The Hoexter Luxator in the septal area of the mandibular molar. The force is directed toward the mesial.

Fig. 2B

The Hoexter Luxator placed at the distal of the mandibular molar with the force directed in a mesial direction.

Fig. 2C

The Hoexter Luxator placed at the mesial of the mandibular molar. The force is directed in a distal direction. With the constant M-D pressure, the root is easily made mobile and removed, thus preserving the buccal and lingual bone.

After the M-D luxation and removal of the individual roots, leaving the intact walls of extracted roots, it is suggested to utilize an osseous regenerative bone graft material. The resorbable graft material is sutured in place, and after the correct healing time, will result in bone regeneration that will support an endosseous implant in the correct supported position (See case presentation Fig. 3). The practitioner will be able to provide the optimal prosthetic replacement – one in occlusal harmony, physiologically-shaped for best function, esthetically pleasing, and easy to maintain.

Fig. 3A

Case Presentation A: Tooth #47 with the temporary crown off, showing caries and broken tooth structure.

Fig. 3B

Tooth #46 with its temporary crown now off, exposing extensive caries and poor prognosis for both #46 and #47.

Fig. 3C

Tooth #46 crown portion divided into two halves.

Fig. 3D

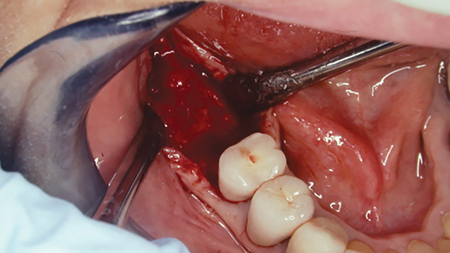

All 4 root sockets and even the osseous septum of #46 are preserved by luxating M-D.

Fig. 3E

All 4 of the roots easily luxated out.

Fig. 3F

Blood clots in the #46 and #47 sockets.

Fig. 3G

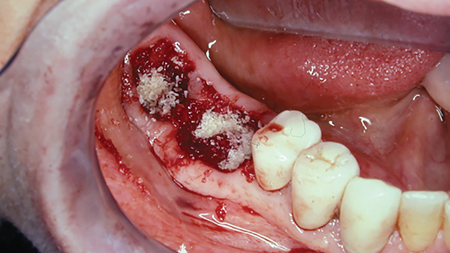

Osseous graft material inserted into the sockets.

Fig. 3H

Resorbable membranes placed over the grafts, before suturing.

Fig. 3I

Lower right area three months post-op.

Fig. 3J

Exposed regenerated bone area 3 months later. Note the full ridge of bone regenerated buccal-lingually as well as mesial-distally.

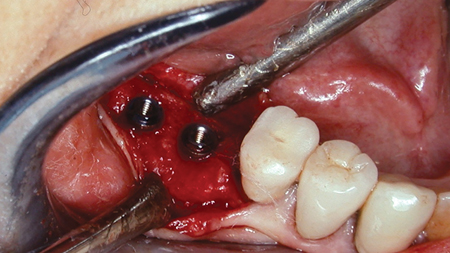

Fig. 3K

Implants inserted at bone level.

Fig. 3L

Implant healing abutments in place.

Fig. 3M

Keratinized area of the mucogingival flap now sutured at the correct level.

Fig. 3N

Final buccal view of the restored prosthesis with healthy keratinized tissue.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

About the Author

David L Hoexter is Director of the International Academy for Dental Facial Esthetics and Clinical Professor of Periodontics and Implantology, Temple University School of Dental Medicine. A Diplomate in the International Congress of Oral Implantology, American Society of Osseointegration, and the American Board of Aesthetic Dentistry, he publishes and lectures nationally and internationally. Dr. Hoexter has been awarded thirteen fellowships, including FACD, FICD, and Pierre Fauchard. His practice in New York City is limited to periodontics, implantology and esthetic surgery. DrDavidLH@gmail.com

David L Hoexter is Director of the International Academy for Dental Facial Esthetics and Clinical Professor of Periodontics and Implantology, Temple University School of Dental Medicine. A Diplomate in the International Congress of Oral Implantology, American Society of Osseointegration, and the American Board of Aesthetic Dentistry, he publishes and lectures nationally and internationally. Dr. Hoexter has been awarded thirteen fellowships, including FACD, FICD, and Pierre Fauchard. His practice in New York City is limited to periodontics, implantology and esthetic surgery. DrDavidLH@gmail.com

To view more articles from the December 2020 issue, please click here!