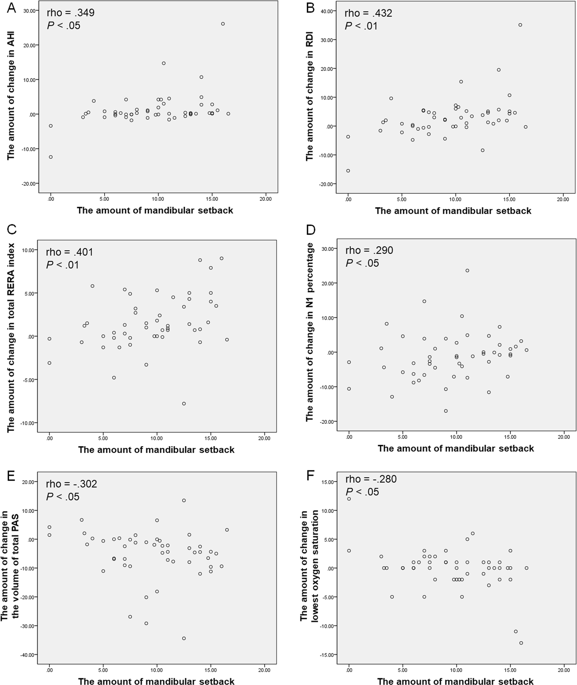

In this prospective study using overnight full PSG and 3D analysis with cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), MSS with or without maxillary surgical movement for skeletal class III patients resulted in significant changes in the sleep parameters of PSG, and volumes of PAS. Symptomatic sleep parameters including the RDI, and total RERA index significantly increased (both P < 0.001; Table 1). Particularly, even though BMI showed significant decrease after surgery (P < 0.001; Table 1), there were significant increases in the RDI, and total RERA index. In all types of PAS except for the nasopharyngeal airway, there were significant decreases in the volume, and the total volume of PAS also decreased significantly (all P < 0.001; Table 1). Several correlations between the sleep parameters in PSG and the amount of mandibular setback might indicate that the larger mandibular posterior movement is, the worse sleep quality becomes. Therefore, we suggest that MSS for skeletal class III patients could worsen sleep quality by increasing RDI, and total RERA index postoperatively. For this reason, it should be emphasized that there is a need to explain the possibility of deterioration of sleep quality after MSS in patients with skeletal class III patients, particularly in patients who require large amounts of mandibular setback.

It is well-known that the volume of total pharyngeal airway after MSS can be decreased. However, two main perspectives exist on the total volumetric change of the pharyngeal airway after MSS with maxillary advancement: significantly reduced11,12,13,14,15 and unchanged16,17,18,19,20,21. In terms of changes in the volume of regional PAS, the majority of articles have reported that the volume of the nasopharyngeal airway does not change significantly after two-jaw surgery14,16,20,21. In the present study, there were significant decreases in total pharyngeal airway volumes, whereas there was no significant change in the volume of the nasopharyngeal airway. These are consistent with previous studies.

Regarding the occurrence of OSA, although there is no evidence of postoperative OSA after MSS within the first 6 months3, 10 patients in this study showed postoperative OSA after MSS with or without maxillary surgery (MSS alone, 7; MSS with LF I, 3). Hasebe et al.1 reported two patients with postoperative OSA after MSS, and in those cases, the amounts of mandibular setback were large. Another study demonstrated that the patients who undergone mandibular setback greater than 5 mm had a higher incidence of mild to moderated OSA7. The mean of the amounts of mandibular setback in patients with postoperative OSA in the present study was also large (11.08 mm); however, one patient underwent MSS for only 4 mm setback. Based on this result, the occurrence of OSA might not always require large amount of mandibular setback. Because the individual host responses to altered biological circumstances such as narrowed upper airway space are different, customized treatment planning and surgery should be required to prevent the occurrence of iatrogenic OSA.

RERA is defined as a sequence of breathing events characterized by increasing respiratory effort, but which does not fulfill criteria for an apnea or hyponea10. On the basis of a report by American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)10, it is suggested that RERAs and hypopneas share a similar pathophysiologic mechanism. Thus, RERA has been included in defining the OSA by using the same frequency of apneas and hypopneas since 1999. Nevertheless, attention has not been focused on RERA as a critical factor for OSA in the field of orthognathic surgery. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study which demonstrated changes in RERA after MSS or bimaxillary surgery. According to a position statement of AASM 201822, as new studies increasingly uncover many negative outcomes associated with OSA, it is essential to accurately perform scoring all respiratory events, including those with arousal, in order to effectively diagnose and treat all patients with OSA. In addition, using PSG results that do not include arousal-based respiratory events of any form when scoring may lead to either lack of adequate diagnosis of OSA, misclassification of OSA severity, or misidentification of another sleep disorder or medical disorder22. In the present study, it was possible to score all respiratory events such as RERA, and consequently, it was observed that total RERA index significantly increased after MSS with or without LF I. Therefore, the authors insist that overnight full PSG possible to measure all respiratory events should be performed to evaluate respiratory changes before and after surgery.

The ESS and PSQI are two of the most widely used self-report questionnaires. The ESS includes eight self-rated questions, and has the purpose to measure a patient’s habitual likelihood of falling asleep in daily life. An ESS score of more than 10 are regarded as the indication of significant sleepiness. The PSQI has 19 self-rated items for evaluation of subjective sleep quality. Higher PSQI scores indicate worse sleep quality. However, neither the ESS nor PSQI was designed for screening of a specific sleep disorder. In addition, Nishiyama et al.23 demonstrated that because ESS and PSQI scores were more affected by psychological symptoms than PSG indices, they should not be used as screening or diagnostic methods for sleep disorders defined by PSG. In the present study, neither the ESS nor PSQI showed significant changes in their scores after surgery, even though postoperative OSA took place in some patients. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing inconsistency in the results of ESS and PSQI with objective sleep measures such as PSG indices. Nevertheless, the ESS and PSQI are warranted before and after surgery, because they can evaluate subjective symptoms. Regarding subjective symptoms, the most noteworthy finding in this study was that the RDI and RERA index could increase after MSS, although subjective symptoms did not show significant changes. Therefore, it is recommended that preoperative and postoperative evaluation by PSG is inevitable to detect these silent changes in patients who require MSS.

The present study differs from previous studies, in that it was a prospective study using preoperative and postoperative overnight full PSG and CBCT data to find out changes in the sleep parameters and volumes of PAS after MSS. In addition, the study also investigated the correlations among PSG, CBCT, and other demographic data and the possibility of the presence of factors affecting the occurrence of OSA. Although Gokce et al.24 also used overnight PSG and computed tomography and reported the changes in PAS and OSA measurements after bimaxillary orthognathic surgery in patients with class III malocclusion, our results differ from their findings. Their study demonstrated that bimaxillary orthognathic surgery caused an increase in the total airway volume and improvement in PSG parameters, and some correlations were reported between computed tomography and PSG parameter measurements. However, they focused on the combined effects of mandibular setback and maxillary advancement and did not present the detailed parameters in overnight full PSG such as the RDI, total RERA index, relative snoring time, and lowest oxygen saturation. Consequently, their results could not reveal distinct correlations between the sleep parameters in PSG and changes in the computed tomography data and could not identify risk factors affecting the occurrence of OSA. Tepecik et al.25 conducted another study that used CBCT data and overnight full PSG to examine the effects of bimaxillary orthognathic surgery on PAS and respiratory function during sleep. Despite presenting RDI, they did not show detailed PSG data and did not identify significant correlations between the PSG parameters and volumetric and area parameters in CBCT. The present study, in addition to the aforementioned distinctions, was performed on more than twice as many cases as those in studies conducted by Gokce et al. and Tepecik et al. Therefore, our report is the largest prospective study to date, comprising 50 patients with skeletal class III malocclusion, and using overnight full PSG for evaluation of sleep-related variables after MSS with or without maxillary surgical movement. Moreover, the present study has the originality, because it supports the finding for the first time that increases in RERA could result from MSS.

Although this is the first study to report significant changes in the RERA index by using preoperative and postoperative overnight full PSG examination prospectively following MSS in patients with skeletal class III patients, the present study has some limitations. This study could not evaluate the long-term effects of MSS. Postoperative PSG examination and CBCT taking were conducted 3 months after surgery, and the 3D volume analyses on PAS were performed by using the CBCT data. Van der Vlis et al.26 quantified the changes in postoperative swelling after orthognathic surgery using serial 3D photographs, and demonstrated that approximately 20% of the initial edema remained after 3 months, and significant decreases in soft tissue swelling still occurred between postoperative 6–12 months. Therefore, residual postoperative swelling in the soft tissue of the pharyngeal airway might affect the results of postoperative PSG and PAS volume measurements. In the future, it is necessary to investigate the long-term effects of MSS for skeletal class III patients on sleep quality or the occurrence of OSA by performing serial overnight full PSG whenever possible.

In conclusion, MSS with or without maxillary movement for skeletal class III patients could worsen sleep quality by increasing the sleep parameters in PSG. Although subjective symptoms may not show significant changes, objective sleep quality in PSG might decrease after MSS. It should be stressed that there is a need to explain the possibility of deterioration of sleep quality after MSS in patients with skeletal class III patients, particularly in patients requiring large amounts of mandibular setback, and overnight full PSG should be performed preoperatively and postoperatively for evaluation of the occurrence of OSA following MSS. Further studies are required to identify the long-term effects of MSS on sleep quality.