In July 1990, the Florida Department of Health reported a possible transmission of HIV from a dentist to five of his patients.1 Though it was unclear if actual transmission of the virus actually occurred, this incidence caused much controversy and worry within dental community.2,3

Dr. Barrera

At the time, health care providers were to follow the CDC’s “Recommendations for Preventing Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis B Virus to Patients,” which recommended that providers with HIV or Hepatitis B must disclose their status to an expert review panel for consideration before the provider may continue to practice.4These guidelines have since been retired by the CDC due to the fact that the risk of transmission of HIV or HBV from provider to patient is minimal during exposure-prone procedures and inconsequential with noninvasive procedures.5,6

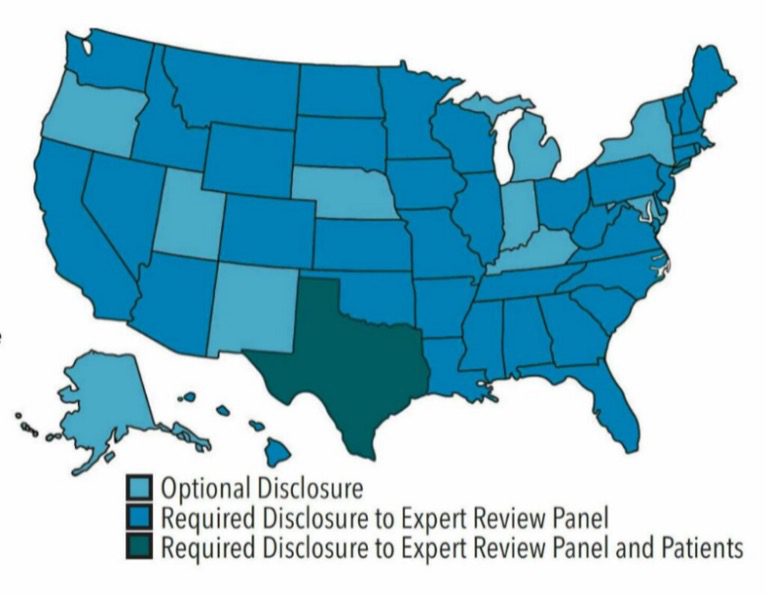

The current CDC guidance makes no mention of patient exposure from dental health care providers because it is a nonissue.6 However, several states have created their own standards and guidelines on how to deal with this situation.

Texas Administrative Code Rule §108.25

Several states, including Texas, require HIV/HBV-positive providers to disclose their status to an expert panel before treating patients. But Texas is the only state that requires these providers to take additional measures which include notifying patients individually.

The Texas Administrative Code Rule §108.25 states, “A dental health care worker who is infected with HIV or HBV and is HbeAg positive shall notify a prospective patient of the dental health care worker’s status and obtain the patient’s consent before the patient undergoes an exposure-prone procedure performed by the notifying dental health care worker.”7

Figure 1. State rules and regulations regarding infectious disease disclosure. Source: The Center for HIV Law and Policy. Guidelines for HIV-Positive Health Care Workers, The Center for HIV Law and Policy. Published March 2008. Updated June 2017. Courtesy of Melanie E. Patterson, RDH, BSDH, and Kimberlynn N. Patzold, RDH, BSDH.

The Texas State Board of Dental Examiners (TSBDE) states that disciplinary actions for noncompliance of infectious disease disclosure to patients may range from a verbal reprimand to license suspension.

It is safe to say that this rule is outdated and discriminatory as it carries the possibility of serious consequences to providers. Mandatory disclosure to patients could have major repercussions for the dentist, such as loss of practice, prejudice toward the provider, and fewer career and educational opportunities.

The impact of advances in anti-viral drugs on management of the infected health care worker

HIV

Development of one of the newer classes of antiretroviral drugs (integrase strand transfer inhibitor agents) has been a major step forward in management of the disease. These drugs are currently viewed as optimal for initial therapy as they are highly effective at virological suppression and are extremely well tolerated. Viral suppression can make the HIV viral load so low that it becomes undetectable in the bloodstream, and therefore untransmutable to another person.8

In 2012, the FDA approved the use of the medication Truvada as a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-negative individuals who are at high risk of acquiring HIV. Today, there are two approved oral medications and 1 injectable treatment for use as PrEP.8

With the progress that has been made towards HIV treatment & prevention, it is safe to say that the Texas Administrative Code Rule §108.25 is antiquated and does nothing to further patient safety or public health.

Hepatitis B

The outstanding protection provided by the Hepatitis B vaccine has shown to have protection lasting for up to 30 years. This was the first important step in reducing the number of health care workers infected with HBV and therefore reducing risk of onward transmission to patients.9 This adds to the case that the Texas Rule is outdated and unnecessary as the risk of Hepatitis B transmission is low.

Looking Ahead

When we take an overall look at the situation, one could argue that adherence to universal precautions alone renders the Texas rule obsolete and discriminatory. Additionally, it is inconsistent that dentists have to disclose personal health information just because it is HIV or HBV compared to other infectious diseases. The Texas State Board of Dental Examiners did not take the same position when the virus in question was SARS-CoV-2.

According to the Texas Dental Association, the Texas State Board of Dental Examiners requires dentists and team members testing positive for COVID-19 and having known close contact with patients while positive, to notify those patients. However, the dental team may also be required to protect the team member’s confidentiality under applicable privacy laws.10 Why would these same laws not be applicable if the dentist was instead positive for HIV or HBV? Especially when HIV and HBV transmission is much less likely to occur in a dental setting. This is evidence that the Texas Administrative Code Rule §108.25 is discriminatory and should be abolished.

My hope is that we use the updated research to abolish rules like the outdated Texas Administrative Code Rule §108.25 so that all health care providers and students have an equal opportunity to treat patients without fear of prejudice or discrimination.

Dr. Alex Barrera is a general dentist at Legacy Community Health in Houston, Texas. He graduated in 2017 from the University of Texas School of Dentistry at Houston and is a member of various organizations including the American Dental Association, Hispanic Dental Association, Greater Houston Dental Association, and the Houston Equality Dental Network. He currently serves as the chair of the New Dentist Committee for the Hispanic Dental Association and is on the ADA Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention. Dr. Barrera is the current president of the Houston Equality Dental Network which allows him to be an advocate for LGBTQ+ care in dentistry. Dr. Barrera is a certified yoga teacher and uses mindfulness and meditation to help better treat patients with dental phobias. In his spare time, he enjoys reading, cooking and traveling.

References:

- “Guidelines for HIV-Positive Health Care Workers, the Center for HIV Law & Policy (2008).” Guidelines for HIV-Positive Health Care Workers, The Center for HIV Law & Policy (2008) | The Center for HIV Law and Policy, 1 Mar. 1970, https://www.hivlawandpolicy.org/resources/guidelines-hiv-positive-health-care-workers-center-hiv-law-policy-2008.

- Brown, David. “The 1990 Florida Dental Investigation: Theory and Fact.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 124, no. 2, 1996, p. 255., https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-124-2-199601150-00010. Accessed 16 Apr. 2022.

- Jaffe, Harold. “Lack of HIV Transmission in the Practice of a Dentist with AIDS.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 121, no. 11, 1994, p. 855., https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00005. Accessed 18 Apr. 2022.

- “Recommendations for Preventing Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Hepatitis B Virus to Patients during Exposure-Prone Invasive Procedures.” MMWR. Recommendations and Reports : Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1648165/.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for preventing transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus to patients during exposure-prone invasive procedures. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40(RR08):1–9.

- “Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 10 Sept. 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/summary-infection-prevention-practices/index.html.

- Texas Administrative Code, 22 Tex. Admin. Code § 110.11, 2010, https://texreg.sos.state.tx.us/public/readtac$ext.TacPage?sl=R&app=9&p_dir=&p_rloc=&p_tloc=&p_ploc=&pg=1&p_tac=&ti=22&pt=5&ch=108&rl=25. Accessed 18 April. 2022.

- “About PrEp.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 20 Apr. 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep/about-prep.html.

- Barrigar, Diana L, et al. “Hepatitis B Virus Infected Physicians and Disclosure of Transmission Risks to Patients: A Critical Analysis.” BMC Medical Ethics, vol. 2, no. 1, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-2-4.

- Tsbde Covid-19 Emergency Rule, https://www.tda.org/covid-19/tsbde-covid-19-emergency-rule.