Abstract

Background

In the context of evolving dental materials and techniques and a national agenda to phasedown use of dental amalgam, estimates of dental amalgam placement are necessary for monitoring purposes.

Methods

Numbers of amalgam and composite posterior restorations from 2017 through 2019 were calculated using retrospective dental claims analysis of privately insured patients. Kruskal-Wallis and multilevel, multivariable negative binomial regression models were used to test for differences in rates of amalgam and composite restoration placement by age group, sex, urban or rural area, and percentage race and ethnicity area distribution. Statistical significance was set at 0.05, with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for false discovery rate.

Results

The rate of amalgam restorations declined over time from a mean of 6.29 per 100 patients in 2017 to 4.78 per 100 patients in 2019, whereas the composite restoration rate increased from 27.6 per 100 patients in 2017 to 28.8 per 100 in 2019. The mean number of amalgam restorations placed per person were lowest in females compared with males, in urban areas compared with rural areas, and in areas with more than 75% non-Hispanic White residents.

Conclusions

Amalgam restoration placements in privately insured people in the United States declined from 2017 through 2019. Amalgam restoration placements may be unevenly distributed by location.

Practical Implications

Achieving further declines of dental amalgam use may require changes to insurance coverage, incentives, and provider training as well as augmented disease prevention and health promotion efforts. These efforts should focus particularly on groups with high caries risk or higher rates of amalgam placement.

Key Words

- Dye B.A.

- Thornton-Evans G.

- Li X.

- Iafolla T.J.

,

,

- Afaneh H.

- Kc M.

- Lieberman A.

- et al.

,

Oral health in America: advances and challenges. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Caries is more prevalent in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children and adults than non-Hispanic White or Asian children and adults,

- Dye B.A.

- Thornton-Evans G.

- Li X.

- Iafolla T.J.

,

rural than urban,

- Afaneh H.

- Kc M.

- Lieberman A.

- et al.

lower income than higher income, and less educational attainment than more educational attainment.

Oral health in America: advances and challenges. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Physical factors such as oral hygiene, diet, tobacco use, fluoride intake, and genetics as well as health conditions affect risk of caries. Sociocultural factors such as acculturation, dental anxiety, language proficiency, and health-seeking norms can also affect caries management.

- Atkins R.

- Bluebond-Langner M.

- Read N.

- Pittsley J.

- Hart D.

,

,

- Yoon H.

- Jang Y.

- Choi K.

- Kim H.

Neighborhood characteristics may affect people’s oral health as well.

One such characteristic is fluoridated water.

Community water fluoridation varies by geographic area, and as of 2018, only 63.4% of the US population received fluoridated water.

Another factor is the type and location of grocery stores, which influence sugar consumption and caries rates.

- Broomhead T.

- Ballas D.

- Baker S.R.

,

- Tellez M.

- Sohn W.

- Burt B.A.

- Ismail A.I.

A third factor is access to care; there is significant geographic variation in dental care providers, with shortages particularly common in rural areas

- Nasseh K.

- Eisenberg Y.

- Vujicic M.

and in neighborhoods with high percentages of Black residents.

- Liu M.

- Kao D.

- Gu X.

- Holland W.

- Cherry-Peppers G.

Lower neighborhood socioeconomic status is associated with lower self-rated oral health

- Borrell L.N.

- Taylor G.W.

- Borgnakke W.S.

- Woolfolk M.W.

- Nyquist L.V.

and dental care use.

- Atkins R.

- Sulik M.J.

- Hart D.

Although these findings may be explained partly by fewer dentists in disadvantaged neighborhoods,

- Liu M.

- Kao D.

- Gu X.

- Holland W.

- Cherry-Peppers G.

they may also reflect neighborhood differences in diffusion and clustering of oral health–seeking behavior, norms, and health information.

- Borrell L.N.

- Taylor G.W.

- Borgnakke W.S.

- Woolfolk M.W.

- Nyquist L.V.

- Worthington H.V.

- Khangura S.

- Seal K.

- et al.

There is low certainty evidence that composite restorations have a higher risk of failure and of secondary caries than amalgam restorations.

- Worthington H.V.

- Khangura S.

- Seal K.

- et al.

,

- Moraschini V.

- Fai C.K.

- Alto R.M.

- Dos Santos G.O.

The higher failure rate for composite restorations may be attributable in part to technique

- Moraschini V.

- Fai C.K.

- Alto R.M.

- Dos Santos G.O.

; composite is considered more technique sensitive and takes more time to place.

- Bailey O.

- Vernazza C.

- Stone S.

- Ternent L.

- Roche A.-G.

- Lynch C.

Advantages of composite restorations include adherence to tooth structure, more conservative cavity preparation, and a visual match to teeth.

- Worthington H.V.

- Khangura S.

- Seal K.

- et al.

,

- Zabrovsky A.

- Neeman Levy T.

- Bar-On H.

- Beyth N.

- Ben-Gal G.

Lastly, unlike amalgam, there are no mercury-related concerns with respect to composites. In 2013 the United States signed the Minamata Convention on Mercury, a global agreement on environment and health that stipulates that use of dental amalgam should be phased down.

- Araujo M.W.B.

- Lipman R.D.

- Platt J.A.

Although there is an absence of evidence of direct negative health effects from dental amalgam, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that populations at highest risk of harm from mercury exposure avoid placement of dental amalgam restorations when possible and appropriate.

- Robison V.

- Wei L.

- Hsia J.

including caries treatment by race and ethnicity,

- Dye B.A.

- Thornton-Evans G.

- Li X.

- Iafolla T.J.

,

,

- Liu M.

- Kao D.

- Gu X.

- Holland W.

- Cherry-Peppers G.

income, educational attainment, and health insurance status.

Cost may affect patients’ dental care decision making owing to commonly higher out-of-pocket costs for composite resin restorations than amalgam restorations.

For example, a 2018 survey of US dentists reported that average fees for resin posterior restorations ranged from $189.73 through $340.48, whereas fees for amalgam restorations ranged from $145.77 through $255.12.

Even after controlling for tooth and carious lesion characteristics, rates of amalgam placement vary significantly by dental insurance, geographic location within the United States, and race.

- Makhija S.K.

- Gordan V.V.

- Gilbert G.H.

- et al.

- Makhija S.K.

- Gordan V.V.

- Gilbert G.H.

- et al.

Dentists’ restoration material choice has been reported to be shaped by clinical considerations, material properties, and their comfort and confidence working with the material as well as patient preference and insurance coverage.

- Lee Pair R.

- Udin R.D.

- Tanbonliong T.

For example, in 2013 members of the Royal College of Dentists of Canada and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry were more likely to choose amalgam for Class II restorations or medically compromised or developmentally delayed patients or if they accepted government-funded patients.

- Varughese R.E.

- Andrews P.

- Sigal M.J.

- Azarpazhooh A.

A 2014 survey of American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry members found that in addition to factors related to caries risk and patient insurance coverage, dentists’ perceptions of the environmental impact of amalgam waste also influenced their likelihood to choose amalgam over other materials.

- Bakhurji E.

- Scott T.

- Sohn W.

Dentists’ choices of restoration materials also have been reported to be influenced by their training,

- Varughese R.E.

- Andrews P.

- Sigal M.J.

- Azarpazhooh A.

,

sex,

- Makhija S.K.

- Gordan V.V.

- Gilbert G.H.

- et al.

,

race,

- Bakhurji E.

- Scott T.

- Mangione T.

- Sohn W.

and rurality.

- Bakhurji E.

- Scott T.

- Mangione T.

- Sohn W.

- Lee Pair R.

- Udin R.D.

- Tanbonliong T.

and by 2013 most (51.3%) pediatric dentists it was composite resin.

- Varughese R.E.

- Andrews P.

- Sigal M.J.

- Azarpazhooh A.

An analysis of Midwestern claims data showed an average 3.7% annual decline in number of amalgam restorations placed from 1992 through 2004

- Beazoglou T.

- Eklund S.

- Heffley D.

- Meiers J.

- Brown L.J.

- Bailit H.

such that by 2007, patients received one-half as many amalgam restorations as in 1992.

We are aware of no more recent estimates of the rate of amalgam posterior restoration placement in the United States nor any investigations into whether previously described differences in amalgam placement have persisted. We sought to describe the yearly incidence of amalgam and composite restorations among privately insured patients in the United States. Furthermore, we sought to test whether there were differences by state and territory or race and ethnicity distribution in an area that may have influenced restoration material choice. If significantly higher amalgam restoration placement rates are identified for certain locations or demographic groups, that information could be used to inform strategies to enhance amalgam use phasedown.

Methods

An aggregated deidentified data set was drawn from the dental insurance claims data in the FAIR Health National Private Insurance Claims database with dates of service from January 1, 2017, through December 31, 2019, for those aged 0 through 55 years. We included only patients with complete information in the analysis, excluding 0.19% of patients with a nonvalid location and 0.18% of patients lacking information on sex. This study does not constitute human subjects research and does not require institutional review board oversight.

Table 1Characteristics of the analysis sample, 2017-2019.

The outcomes were nonnormal, so we used Kruskal-Wallis and post hoc Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner to test for differences.

- Hollander M.

- Wolfe D.A.

- Chicken E.

We modeled rate of amalgam restorations per patient in single and multivariable regression models in Stata Version 17.0 (StataCorp). Owing to the high proportion of zeroes and overdispersion in number of amalgam restorations per patient, initially we used zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB). However, none of the independent variables was associated significantly with excess zeroes in the ZINB model, and the Akaike and Bayesian information criterion were lower for a negative binomial (NB) model than the ZINB. Using NB instead of ZINB did not alter the conclusions; the odds ratios were identical or within 0.001 of each other in both model types. Given differences in rates of amalgam restoration placement among states and the conceptual likelihood of unobserved characteristics at the state level, we chose a 2-level regression model to nest observations within the state or territory where the amalgam restoration was placed.

Figure 2Proportion of patients receiving posterior restorations by state, age, and material.

Results

Table 2Proportion of privately insured patients receiving amalgam or composite posterior restorations, 2017-2019.

Table 3Mean number of amalgam or composite posterior restorations per patient, 2017-2019.

Age

Figure 1Proportion of patients receiving each posterior restoration material, by age group.

Sex

Geographic location

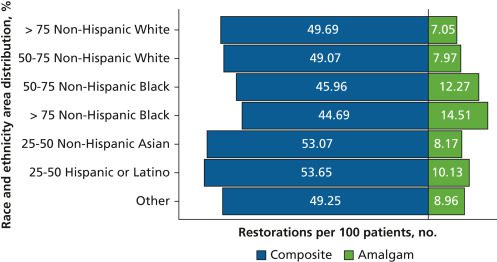

Racial and ethnic area distribution

Figure 3Mean number of posterior restorations per 100 patients, by race and ethnicity area distribution.

Modeling

Table 4Odds of higher count of amalgam posterior restorations per patient, 2017-2019.

Discussion

- Beazoglou T.

- Eklund S.

- Heffley D.

- Meiers J.

- Brown L.J.

- Bailit H.

there appeared to be far fewer amalgam restorations placed per person for every age group except the youngest. The decline in amalgam restorations in the United States mirrored international trends.

- Aggarwal V.R.

- Pavitt S.

- Wu J.

- et al.

,

- Broadbent J.

- Murray C.

- Schwass D.

- et al.

, Countries that are signatories to the Minamata Convention, including the United States, are phasing down the use of dental amalgam.

- Araujo M.W.B.

- Lipman R.D.

- Platt J.A.

,

US Environmental Protection Agency.

about amalgam restoration placement in pregnant and breastfeeding people. Another population of concern is children.

,

US Environmental Protection Agency.

In this data set, dental patients younger than 6 years had the lowest ratio of amalgam restorations to composite restorations. However, children had a significantly higher rate of amalgam restorations per patient than other dental patients (P

Our study also found a statistically significant relationship between dental office location characteristics and posterior restoration materials used. Rural areas showed higher amalgam use than urban areas. The areas with the highest proportions of non-Hispanic Whites had the lowest use of amalgam for posterior restorations, whereas amalgam use increased with increasing proportions of non-Hispanic Blacks. This finding adds to the growing literature about area characteristics associated with differences in oral health care.

- Estrich C.G.

- Lipman R.D.

- Araujo M.W.B.

There is a conceptual difference between how many amalgam restorations are placed per year vs how many are present in teeth at any given point. This also may be related to the higher rates of failure and risk of secondary caries for resin-based composite restorations compared with amalgam restorations,

- Worthington H.V.

- Khangura S.

- Seal K.

- et al.

such that over time composite restorations may be replaced with amalgam restorations. However, this seeming discrepancy in findings between the 2 data sets also may be indicative of differences between effects observed at the neighborhood and individual levels.

changing patient preferences, population shifts in clinical factors such as caries lesion severity, changes in insurance policies, or some combination of influences. A limitation of our study was that we did not have access to individual-level data. We were unable to explore clinical reasons such as caries risk or patient preferences such as cost for observed differences. The differences in restoration material we found via characteristics of the dental care provider’s location undoubtedly are confounded by unmeasured social, physical, and economic differences. Another limitation of our study was that it included only privately insured patients. As insurance can be expected to affect dental care and only one-half of dentate adults in the United States had private dental coverage during the studied period,

- Blackwell D.L.

- Villarroel M.A.

- Norris T.

these results may not be generalizable to those in the US population without insurance. We excluded 0.37% of the sample for missing information, which may have introduced bias. In addition, areas were created via stratifying by sex and age group per geozip, which may not be in perfect concordance with patients’ actual neighborhoods. Lastly, restorations with materials other than amalgam or resin-based composite are not included.

A strength of this study was that it was derived from claims data and therefore was unlikely to be affected by acquiescence or reporting biases. In addition, these estimates were based on dental claims for patients from more than 70 private insurers from every US state, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. Lastly, they represented the most up-to-date information on US dental practice patterns regarding amalgam posterior restorations of which we are aware. This type of information is vital to evaluating the United States’ compliance with Minamata Convention obligations. Continued phasedown of dental amalgam use may require changes to insurance coverage and reimbursement rates for nonamalgam-based restorative materials and increased training and funding opportunities for development of restorative materials, especially materials suitable for posterior restorations. Most important is the need to increase disease prevention and health promotion efforts, particularly among groups with high caries risk.

Conclusion

Use of amalgam as a restorative material by US dentists was consistent with the Minamata Convention phase down of the use of dental amalgam. There is both geographic and demographic variation in placement of dental amalgam within the United States. Additional research that enables a fuller understanding of the factors contributing to this could facilitate continued phasedown. Nonetheless, there may be circumstances in which amalgam is of clinical benefit, but there does appear to have been a nationwide decrease in the use of amalgam as a restorative material.

References

Dental caries and sealant prevalence in children and adolescents in the United States, 2011-2012.

NCHS Data Brief. 2015; 191: 1-8

Update on the prevalence of untreated caries in the US adult population, 2017-2020.

JADA. 2022; 153: 300-308

Rural-urban disparities in the distribution of dental caries among children in south-eastern Louisiana: a cross-sectional study.

Rural Remote Health. 2020; 20: 5954

Oral health in America: advances and challenges. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Adolescents as health agents and consumers: results of a pilot study of the health and health-related behaviors of adolescents living in a high-poverty urban neighborhood.

J Pediatr Nurs. 2010; 25: 382-392

Regular dental visits and dental anxiety in an adult dentate population.

JADA. 2005; 136: 58-66

Preventive dental care utilization in Asian Americans in Austin, Texas: does neighborhood matter?.

Int J Enviro Res Public Health. 2018; 15: 2261

Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health.

Am J Public Health. 2001; 91: 1783-1789

Community water fluoridation. Centers for Disease and Prevention.

Neighbourhoods and oral health: agent-based modelling of tooth decay.

Health Place. 2021; 71102657

Assessment of the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and dental caries severity among low-income African-Americans: a multilevel approach.

J Public Health Dent. 2006; 66: 30-36

Geographic access to dental care varies in Missouri and Wisconsin.

J Public Health Dent. 2017; 77: 197-206

Oral health service access in racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods: a geospatial analysis in Washington, DC, USA.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19: 4988

Perception of general and oral health in White and African American adults: assessing the effect of neighborhood socioeconomic conditions.

Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004; 32: 363-373

The association of individual characteristics and neighborhood poverty on the dental care of American adolescents.

J Public Health Dent. 2012; 72: 313-319

Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent posterior teeth.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021; 8: CD005620

Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

J Dent. 2015; 43: 1043-1050

Amalgam phase-down, part 1: UK-based posterior restorative material and technique use.

JDR Clin Trans Res. 2022; 7: 41-49

Next generation of dentists moving to amalgam-free dentistry: survey of posterior restorations teaching in North America.

Eur J Dent Educ. 2019; 23: 355-363

Amalgam: impact on oral health and the environment must be supported by science.

JADA. 2019; 150: 813-815

FDA issues recommendations for certain high-risk groups regarding mercury-containing dental amalgam. US Food and Drug Administration.

Racial/ethnic disparities among US children and adolescents in use of dental care.

Prev Chronic Dis. 2020; 17: E71

Cavity filling cost: how much does a cavity filling cost? CostHelper.

Survey of dental fees. American Dental Association.

Practitioner, patient and carious lesion characteristics associated with type of restorative material: findings from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network.

JADA. 2011; 142: 622-632

Materials used to restore class II lesions in primary molars: a survey of California pediatric dentists.

Pediatr Dent. 2004; 26: 501-507

An assessment of direct restorative material use in posterior teeth by American and Canadian pediatric dentists, I: material choice.

Pediatr Dent. 2016; 38: 489-496

Factors associated with pediatric dentists’ choice of amalgam: choice-based conjoint analysis approach.

JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019; 4: 246-254

The transition from amalgam to other restorative materials in the US predoctoral pediatric dentistry clinics.

Clin Exp Dent Res. 2019; 5: 413-419

Materials and techniques for restoration of primary molars by pediatric dentists in Florida.

Pediatr Dent. 2002; 24: 326-331

Dentists’ perspective about dental amalgam: current use and future direction.

J Public Health Dent. 2017; 77: 207-215

Economic impact of regulating the use of amalgam restorations.

Public Health Rep. 2007; 122: 657-663

Trends in dental treatment, 1992 to 2007.

JADA. 2010; 141: 391-399

FH NPIC® claims data. FAIR Health.

- Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature (CDT). American Dental Association,

2020 Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing.

J Royal Stat Soc. 1995; 57: 289-300

Nonparametric Statistical Methods.

John Wiley & Sons,

2013Assessing the perceived impact of post Minamata amalgam phase down on oral health inequalities: a mixed-methods investigation.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2019; 19: 985

The dental amalgam phasedown in New Zealand: a 20-year trend.

Oper Dent. 2020; 45: 255-264

- Lessons From Countries Phasing Down Dental Amalgam Use. United Nations Environment Programme,

2016 US Environmental Protection Agency.

Dental amalgam restorations in nationally representative sample of US population aged ≥15 years: NHANES 2011-2016.

J Public Health Dent. 2021; 81: 327-330

Regional variation in private dental coverage and care among dentate adults aged 18-64 in the United States, 2014–2017.

NCHS Data Brief. 2019; 336: 1-8

Biography

Dr. Estrich is a manager of epidemiology and biostatistics, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL.

Ms. Eldridge is a research associate, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL.

Dr. Lipman is the senior director of Evidence Synthesis and Translation Research, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL.

Dr. Araujo is the chief science officer and chief executive officer, American Dental Association Science and Research Institute, Chicago, IL.

Article info

Publication history

Published online: March 30, 2023

Accepted:

February 6,

2023

Received in revised form:

January 23,

2023

Received:

October 25,

2022

Publication stage

In Press Corrected Proof

Footnotes

Disclosures. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

This work was supported using internal resources of the American Dental Association Science and Research Institute.

Research for this article is based on dental claims data compiled and maintained by FAIR Health. The authors of this article are responsible for the research and conclusions reflected herein. FAIR Health is not responsible for the conduct of the research or for any of the opinions expressed in this article.

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2023.02.005

Copyright

© 2023 Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of the American Dental Association.

ScienceDirect

Access this article on ScienceDirect